There are many technical definitions for Web 2.0, but in 2006, publisher Tim O’Reilly boiled it down to a single phrase: an application that gets better the more people use it. As he explained:

Google gets smarter every time someone makes a link on the Web. Google gets smarter every time someone makes a search. It gets smarter every time someone clicks on an ad. And it immediately acts on that information to improve the experience for everyone else.[1]

This isn’t just true about Google. The more videos you rate on Netflix, the better job it does recommending films—not just to you, but to all its users. The more books in your LibraryThing library, the easier it is for people to find books they might like. These systems provide more than personalized experiences; they also provide community value.

What does a cultural institution look like that gets better the more people use it? Many people—professionals and visitors alike—see museums as getting worse the more people use them. More people means crowds between a visitor and her aesthetic experience. More people means more noise, more fingerprints, more mess. While staff members celebrate high visitation as a sign of institutional health, they privately recommend that friends visit during quiet hours for a better experience.

But what if it was possible to design an institution that enabled visitors to enhance each other’s experiences? The previous chapter addressed tools that get better the more individuals use them; this chapter explores ways to enhance visitor experiences via interactions with others. This is “me-to-we” design, which enables cultural institutions to move from personal to social engagement.

Designing experiences that get better the more people use them is not simply a question of providing experiences that are well suited to crowds. While many people cite social engagement as a primary reason for visiting museums, they don’t necessarily want to spend their entire visit talking or interacting with other visitors in groups. Successful me-to-we experiences coordinate individuals’ actions and preferences to create a useful and interesting collective result. Technologists often call this “harnessing collective intelligence.”

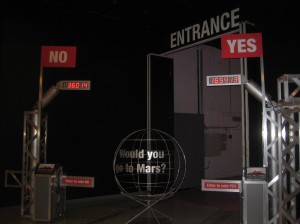

Consider the Ontario Science Centre’s Facing Mars traveling exhibition. The exhibition opened and closed with a question: “Would you go to Mars?” and visitors entered and exited through turnstiles labeled “yes” and “no.” This personalized experience primed visitors emotionally for the exhibit based on their personal identities. But Facing Mars went one step further. Above each turnstile an LED display showed the aggregate number of visitors who selected “yes” or “no” to date. Each visitor could watch the number tick up as she walked through her selected turnstile. She had a personal experience answering the question, and her answer made a visible contribution to the exhibition and affected the experience of others.

While the exhibition was on display at the Ontario Science Centre, about two-thirds of entering visitors answered “yes” they would go to Mars. At the exit, the numbers were reversed and only one-third still wanted to visit the red planet. Collective intelligence told visitors something very simple: lots of people think they want to go to Mars, but when they find out what’s really involved, they change their minds. This insight is interesting and surprising. And, it was more powerfully conveyed since it was based on data that visitors knew they had contributed to. This message could not be as convincingly offered in label text as it was via the displays, even if it was an underlying focus of the whole exhibit.

Visitors entered Facing Mars either through the “Yes” or “No” turnstile. The setup was duplicated at the exit so visitors would vote again on their way out.

The LED displays made visitors aware of themselves as part of a larger social network of visitors—some like them, some unlike them. For visitors whose minds were changed by the exhibition, the displays offered confirmation of a shared social shift. For visitors who did not experience a change of heart, the displays provided information that may have encouraged them to reflect on what made them unique. The LED displays created a social context for what was already a compelling personal experience by networking the individual selections of each visitor.

The Network Effect

The Facing Mars turnstiles are an example of the network effect, which translates individual actions into community benefits. The network effect is the backbone of social networks. Here’s how it works:

- Individuals have personalized interactions. They create content, make choices that generate data, or provide personal information in the form of profiles.

- An internal algorithm makes connections among the individuals. That can mean sorting profiles by interests or types, setting relationship levels among different individuals, or simply aggregating the content.

- The networked content is displayed or provided back to the individuals. In examples like Facing Mars or comment boards, everyone gets access to the same content. In systems like LibraryThing or Pandora (see page 46 and page 51 respectively), the content is customized to individuals to provide personalized recommendations or content streams.

The New York Hall of Science’s exhibit Near is a good physical demonstration of how these networks work.[2] Near is a floor-mounted exhibit. When you step on the Near mat, you become a node, represented by your location on the mat. Your movement is the individual action. When other people step on the mat, lighted lines indicate abstracted relationships with other nodes/people on the mat. The lights are the content output. The exhibit employs a simple algorithm: it draws a line between each node and the node nearest to it. If there are just two people, there will be two lines, one from me to you, and one from you to me. If there are several people, there will be several lines, and not all nodes will be in reciprocal relationships with just one other close node. As people move around the mat, the lines change as they get closer to some people and further from others. The more people moving on the mat, the more the light display indicates the dynamic ways that nodes can be related in a complex system.

Beyond illustrating how networks work, Near demonstrates the power of the network effect in designing multi-person exhibits. The exhibit is flexible and scalable for groups who drift in and out. The activity of walking on the mat is individual, so individuals don’t have to worry about how others’ contributions might disrupt their personal experience. But the exhibit immediately and transparently communicates the benefits of multiple individuals all acting at once, encouraging group play. Near doesn’t require visitors to explicitly work together, but it provides additional rewards when people do so.

The Balancing Act Between Networked and Social Experiences

Designing high-quality experiences for multiple users is no easy task, especially if an exhibit has to work as well for thirty people as it does for two or must accommodate both pre-defined and casual groups of users. The most scalable way to do this is to provide many optional individual actions that can add to a social experience but that are not essential to the exhibit’s success. Rather than designing exhibits with fixed roles that specific numbers of visitors must fill at the same time, you might design more flexible ways for non-participating visitors to engage peripherally in single-user interactives as spectators, helpers, or partners. For example, some museums have “quiz game” style exhibits at which individuals can answer questions in front of a large projection. While only one visitor can hold a controller, a larger group can crowd around to help him answer questions and play along.

In Near and Facing Mars, network effects allow any number of visitors’ individual actions to combine toward productive shared outputs. To make this work, designers have to respect individuals’ actions and personal space so they feel confident jumping into a social environment. If Near had required visitors to get uncomfortably close to generate connections, fewer people may have felt comfortable playing with each other on the mat.

This principle is also at work in some of the most successful multi-touch table installations in museums. Well-designed multi-touch tables promote both personal exploration and interpersonal play. People feel comfortable crowding around these tables and engaging with each other because each person can control his own zone of the table with his hand. No one can take over “your spot” but there are often opportunities to work collaboratively to beneficial group results. Everyone comes to the exhibit equally, and it’s easy to look up from what you are doing to check out what’s going on at another station or talk to another visitor. By entering via their own safe space, visitors are more willing to engage with others.

Recall the stages of social participation introduced in Chapter 1. Most unfacilitated social engagement among visitors starts with a stage three or stage four experience. The Facing Mars turnstiles offered a stage three polling experience, in which individual users’ actions were networked and presented to each other in aggregate. Most user-generated content experiences in cultural institutions are also on stage three. Visitors can produce content (write their own labels, produce stop-motion videos, etc.) and other visitors can view them. Stage three experiences tend to promote social awareness but not necessarily social engagement among visitors. I can’t respond specifically to the person who wrote the provocative message on the comment board—I can only respond to the masses. Others can see my contribution, but they can’t talk directly to me.

The difference between stage three and stage four lies in the extent to which the institution serves as a platform that mediates direct social engagement among users. For example, imagine equipping the Facing Mars entrance turnstiles with a system that offers each visitor a sticker indicating whether they chose yes or no.[3] Now, visitors who wear the stickers would see not only the aggregate responses of visitors-to-date, they can also approach other visitors in real-time in the exhibition and say, “Hey, I chose yes too!” or “Huh. I chose yes and you chose no. What makes us different?” This is an experience that cannot happen based solely on the LED displays (stage three). It also cannot happen based solely on people making selections privately for themselves (stage two).

Stage four experiences are most useful when cultural institutions want to promote direct interpersonal engagement, or when visitors would benefit from knowing more about the unique background or profile of the other visitors using the platform. Visitors may not need a stage four experience to read each other’s memories about a historic event or find out how they compared to others in a poll. But in situations that feature opinionated content or recommendations, people like to know who’s speaking.

CASE STUDY: A Networked Show at the Anne Frank Museum

One of the best illustrations of the hazy boundary between stage three and stage four experiences is the Free2Choose experience at the Anne Frank Museum in Amsterdam.[4] Free2choose is a very simple interactive show in which visitors vote on their stances on issues related to freedom. It is one room, with a long, semi-circular bench with cushions and room for about 30 people to sit and stand. Every few feet on the bench, there is a small voting box about the size of a light switch with two buttons on it, one red and one green.

The visitors on the bench face a large projection screen that plays a fixed loop. First, a one-minute video clip presents an issue (for example, whether students should be allowed to wear headscarves to school). Then, a statement pops up: “Students should be allowed to wear religious symbols in school.” Visitors see a ticking countdown and are told to vote by pressing either the green (yes) or red (no) button on the voting box. At the end of the countdown, the results are shown for both “Visitors Now” and for “All Visitors” (meaning all visitors to date).

The Now vs. All display makes Free2Choose a powerful social experience. When you take a poll alone or walk into Facing Mars, there’s no suspense about the outcome. I voted yes for going to Mars, and then I saw that 65% of other visitors over time agreed with me. In Free2choose, I voted yes for headscarves, saw that 65% of all visitors agreed with me, but also saw that only 40% of the people currently in the room agreed with me. When the results for “Visitors Now” differed greatly from those of “All Visitors,” the surprise was audible. I was in one group where 100% of us voted that Protestants should be able to parade through Catholic areas of Northern Ireland, and we looked around with curiosity and complicity when we saw that only 60% of “All Visitors” agreed with us. Every group was different, so every outcome was different.

Free2choose is powerful because it introduces social tension. When I voted in the minority, I felt that I was in the minority not just conceptually but physically, in that crowd, in real-time. Because the room was often full, I found myself looking for people “like me” in the crowd. But I had no way to identify them in the faceless group of button-pushers.

And that’s where the social dimension of Free2choose (and stage three experiences generally) falls short. There is no component to the Free2choose exhibition that highlights the specific selections made by individuals in the room, and no vehicle to incite conversation among differing groups. When I visited Free2Choose, there was lots of buzz in the room—but only in whispers among familiars. At one point, I stood next to a group of British visitors who voted that flag burning should be illegal. I had voted the opposite. We were standing close enough—a few inches apart—to see each other hit the button, but I was not comfortable asking them about their decision or having a discussion about our different choices.

How could Free2choose encourage visitors to talk with each other directly about the issues? Here are some design suggestions that could foster stage four or five engagement:

- Voting could be more public. When the results are shown, spotlights in the ceiling could illuminate areas of the room in different colors corresponding to who selected yes or no.

- Instead of voting in place, visitors could be directed to vote by moving to one side of the room or another.

- After the results are shown, the screen could instruct visitors to find someone in the room who voted differently from them, or just to ask their neighbor what they think about the issue or the results.

- Visitors could be instructed to share voting stations and to have a brief discussion to come to a consensus vote. As it was, there were too few stations and people awkwardly looked on as others used them.

Not everyone would want to go to the next level and have a conversation with strangers, but based on their conversations with companions, it was clear that some visitors were deeply engaged and did want to talk about the results. In an international city like Amsterdam, in a museum focused on one girl’s extreme story that has touched the whole world, there is an enormous opportunity to go to the next level and facilitate cross-cultural discussion. As it stood, I had an interesting time comparing the results from different groups in my head. But I didn’t understand why those groups were different, and I didn’t gain more insight into how different people think about complicated human rights issues. I wanted more than just a fun interactive—I wanted to understand the other people in the room. It would have made for an extraordinary and unique experience in line with the overall mission of the Anne Frank House.

Free2choose is a perfect example of the limits of a stage three experience. Even though you are densely packed in a room with other people expressing opinions about important issues, you don’t turn to your neighbor and start talking. The stigma is too great, and there is not enough scaffolding to help you cross the social barriers. You vote and see the results (stage three), but the voting mechanism is not a social object that mediates and motivates engagement with others (stage four). And so, even though you are all together in the same room, grappling with tough issues, you will never launch into group discourse (stage five).

Finding Your Own Way In

Not every exhibit benefits from being more socially networked. The Exploratorium’s Spinning Blackboard exhibit is a good example of an exhibit that had to shift away from a networked setup to provide a high-quality multi-user experience. Spinning Blackboard invites visitors to make patterns in a spinning disc of sand. In the exhibit’s original version, visitors all worked on the same disc. They were able to easily and unthinkingly mess up each other’s patterns, which led both to confusion and frustration. The shared platform hindered rather than improved individual experiences.

The exhibit was redesigned as several adjacent spinning discs, allowing visitors to individually create their own sand patterns while remaining in discussion range with other pattern makers. This reasserted the primacy of the “me” experience while still making social engagement possible. This redesign resulted in a significant increase in number of patterns created, presumably because people were less frustrated by disruption and more able to fulfill their exploratory interests.[5]

The original version of Spinning Blackboard suffered from too many hands in the pot. Photo (c) Exploratorium.

In this case, the Exploratorium staff saw their goal as making it easier for visitors to control the sand patterns. But they could have taken a very different approach by prioritizing the social cooperation and competition that occurs when many hands dig in the sand. Consider the multi-player online game Just Letters.[6] Just Letters is an online version of refrigerator magnets in which you use your cursor to move around letters to make words. There’s no goal or score, but the multi-player environment provides diverse opportunities for people to work together or compete. At any time, there may be as many as twenty people logged in, moving around letters. A group will decide to gather together all the blue letters. Then someone else will start stealing letters to spell his name over and over. Since there’s no way for people to chat with the other players in the game, those who want to work collaboratively have to find creative ways to intuit each others’ goals and help.

The disruptiveness that plagued the original version of Spinning Blackboard is the game mechanic that makes Just Letters unpredictable, lively, and fun. I’m not suggesting that one of these experiences is better than the other, but that it is possible for social friction to generate positive user experiences. It all depends on the values and behaviors you want to promote.

Designing Mediating Technology for Social Experiences

Just Letters has something that Spinning Blackboard does not: the mediating barrier of the Internet. Because people play the game through their own personal computers, they may be more comfortable both disrupting each other’s play and collaborating with strangers than they would be in person. In this way, technology that looks like a social barrier leads instead to social engagement.

We’re all familiar with the way technological barriers can make us more comfortable socializing with strangers—for good and ill. The same comfort that allows people to bare their souls (and lie) on the Web encourages kids to make funny faces through car windows. When you interact with strangers across barriers, you are more willing to engage in ways that might be considered rude or disruptive if you were together in person. This means that if you design the right barrier, you can invite visitors to engage with each other in some unusual and valuable ways.

Two layers of technology mediate Just Letters: the letters and players’ computers. Without these barriers, people are probably too polite to make this kind of interaction possible. If you encountered a similar experience in a museum—a giant magnetic poetry wall, perhaps—people would likely interact with the wall singly or in their pre-determined groups, creating their own poems. I doubt that visitors would often interact in real time with other users of the wall—even to ask nicely if they could borrow a word. The social barriers to interaction among strangers are too high.

But imagine constructing a real-world version of Just Letters with barrier intact. Picture two magnetic poetry walls, back to back, with rods on the inside connecting words on each side. The walls look disconnected, but as soon as you move a word on one side, a word on the other side moves too. Suddenly, you start peeking around the wall, wondering what the heck that other person is doing. You might start coordinating or competing. The physical barrier between you would create a social environment for play, a bridge for stranger-to-stranger interaction.

CASE STUDY: How Internet Arm Wrestling Mediates Social Engagement

The Internet Arm Wrestling exhibit is a fascinating example of how technology-mediated interaction can lead to direct interpersonal engagement in museums. Internet Arm Wrestling was installed in six American science centers in 2004. This exhibit allows people to virtually arm wrestle with people around the country. When you sit down to use it, you grasp a metal arm (meant to simulate your competitor’s arm) and are connected to another visitor at an identical kiosk. This visitor may be a few feet from you in the same science center or hundreds of miles away at another science center. You receive a “go” signal, and then you start pushing. The metal arm exerts a force on your arm equal to the force exerted by your remote partner on his own metal arm. Eventually, one competitor overpowers the other, and the game is over.

What makes Internet Arm Wrestling incredible—and a bit bizarre—is the extent to which strangers feel comfortable socializing around this game. Each player can communicate through a webcam feed to her partner as they play. Early on, some science centers removed the audio functionality of the webcams because some kids yelled obscenities at each other through the cameras.[7]

A visitor at the New York Hall of Science watches his opponent intently as he presses on the metal arm. Photo by Ryan Somme.

I watched piles of kids use this exhibit at the New York Hall of Science in 2007, socializing both at each kiosk and across the kiosks. In some cases, multiple kids would gang up on one kiosk and try to sit on the arm to exert force on it. Kids would push on the arm as hard as they could, then turn their heads to look and laugh at their opponents at the other kiosk, then turn back and shove on. Other times, strangers—adults and kids—would stick out their tongues at each other in the cameras or make funny faces to try to distract their opponents from the task at hand.

Think about how unusual this is. Strangers—adults and children—engaging in silly and competitive social behavior through a set of metal arms. Would you ever challenge an unknown child (or adult, for that matter) to an arm wrestling match in a museum? Would you ever challenge a stranger to an arm wrestling match unprompted, ever? The Internet Arm Wrestling exhibit allows people to enjoy an interpersonal experience that otherwise wouldn’t happen.

The Experimentarium in Denmark took this one step further with EgoTrap, a game visitors can play onsite with their mobile phones. After completing three solo challenges, each player is linked via mobile phone numbers to another who is playing at the same time. The players are instructed to call each other, and then they meet up in person and play the rest of the game together throughout the science center.

This is not quite as risky as it may sound. Mostly intact groups (students and families visitors) play EgoTrap, so players are likely to be paired with classmates or family members. But this game raises an interesting question: if you wanted to invite absolute strangers to engage with each other, could you? That’s what the next case study is all about.

CASE STUDY: Learning with Strangers in The Human Library

The Human Library is an event that gets strangers talking openly and directly with each other about prejudice.[8] The organizers describe Human Library as “a tool to foster peaceful cohabitation and bring people closer together in mutual and careful respect for the human dignity of the individual.” Visitors sign up with a staff member, look through a catalog of stereotypes, pick one of interest, and enter into a 45-minute conversation with a real person who embodies that stereotype. As its organizers put it:

The Human Library works exactly like a normal library – readers come and borrow a ‘book’ for a limited period of time. There is only one difference: the Books in the Human Library are human beings, and the Books and readers enter into a personal dialogue. The Books in the Human Library are people representing groups frequently confronted with prejudices and stereotypes, and who are often victims of discrimination or social exclusion. The ‘reader’ of the library can be anybody who is ready to talk with his or her own prejudice and stereotype and wants to spend an hour of time on this experience. In the Human Library, Books cannot only speak, but they are able to reply to the readers’ questions, and the Books can even ask questions and learn themselves.[9]

A Human Library requires three kinds of people:

- Books who openly and authentically represent certain stereotyped groups (i.e. quadriplegic, Black Muslim, cop, Goth, lesbian)

- Readers who check out the Books for 45-minute to 2-hour discussions

- Librarians who facilitate the whole process

The Human Library was conceived in Denmark in 2000 as a way to engage youth in dialogue about ending violence by encouraging people to meet their prejudices and fears in a safe, fun, facilitated environment. Since then, Human Libraries have been produced all over the world at festivals, in libraries, and in workplaces. While they started as one-off events, Human Libraries have increasingly been included in the regular slate of programming at major libraries and educational facilities. Some institutions have expanded their scope beyond the initial focus on prejudice to provide a peer network for learning. For example, the University of Arkansas’ Fall 2009 Human Library catalog included Books like “Meditation 101” and “Learning about Table Tennis” alongside more traditional volumes like “Christian Female Soldier,” and “I am an Atheist.”[10]

Where evaluated, Human Libraries have been incredibly successful. In an evaluation of a Human Library in Istanbul featuring 21 Books, 481 out of 484 Readers said they would recommend that others try the reading experience.[11] Several readers praised the authentic nature of the encounters as “exciting” and “educational.” One reader said: “I could find common grounds with the advocate of an opinion that I do not agree with :).” Another Turkish reader commented:

I’ve never had a gay friend. It was unbelievably exciting to find myself facing him with his body, opinions and identity. It seems he was not very different from me and especially he was not an alien. From now on, I will not disrupt my communication with the gays, I will enhance it.

A subway ticket inspector Book at a Danish Human Library shared this reflection:

It was very interesting to meet and learn about how these young people experienced us (ticket inspectors) on duty in the trains.

Some of the most frequently asked questions were “Do you have to be a bastard to get a job like yours?,” “Don’t you ever feel sorry for those people who somehow find themselves in a situation without a ticket but needing transportation?,” or “Isn’t it terribly difficult for you to have to do this to other people?.” In several cases they had questions that related to a specific situation they themselves had been involved in. I heard many of the readers’ personal experiences with my colleagues, good and bad. But the advantage of the situation was that I was right there, sitting with them and ready to try to answer their questions. I often had to cut the conversation short when the time ran out.

I especially remember one situation with a young couple, sworn members of the Punk scene with their colourful hair and black leather outfits; we had a very interesting discussion and some more people joined us and started to ask questions. It ended up being 20 people joining in and listening to me babble about my work as “the bad guy who writes out the tickets.[12]

Unlike other networks explored in this chapter, the Human Library does not function on a proximate model. It doesn’t give Readers Books that are most “like them” or related to their lived experience. Instead, it challenges Readers to connect with something foreign and unfamiliar. The value system that underlies the Human Library network is one focused on confronting long-held beliefs and moving outside your comfort zone.

The Librarians play a very special role in making this possible. By serving as connectors instead of delivering content, Librarians can spend their time recruiting new and interesting Books, creating a safe space for Books and Readers, evaluating the experience, and refining the setup, rather than learning how to deliver Book content (less authentically) themselves.

Librarians help eager Readers find Books of interest at a 2009 Human Library in King’s Garden in Copenhagen, Demark. Photo courtesy Human Library.

Librarians also perpetuate the metaphor of the library, which serves as the platform for the social interactions. The Human Library methodology very deliberately mimics traditional library experiences. Human Library spaces are often decorated to simulate libraries, or increasingly, are staged in real libraries. Visitors fill out a special library card, talk with the Librarian, browse the catalog, and spend a significant amount of time with any Book selected. Librarians maintain these conventions, even in contexts like festivals in which they seem a bit absurd. The creators of the Human Library project recognized that libraries are safe places for learning new things. They capitalized on that value to make a risky proposition to users. By framing the whole experience in the context of a library, which has widely understood implicit rules and expectations, they turned something that could have simply been about provocation and bravado into a true learning opportunity.

I worked with a team of graduate students in 2009 who used a similar device in Advice, a temporary exhibition at the University of Washington student center.[13] The students designed an advice booth as part of the exhibition and invited volunteers—some of whom signed up entirely spontaneously—to staff it. As in the Human Library, the advice booth provided a familiar infrastructure (a platform) that made people comfortable giving and getting advice from strangers, including eight year olds, tattoo artists, and money managers.

These platforms—the library cards, the advice booth—may seem artificial, but they are deeply important. Imagine the alternative. Imagine putting out some comfortable couches and a sign that says, “talk to strangers about your prejudices” or “give advice to each other here.” Even in the context of a larger exhibition or comfortable environment, I suspect that very few people would use these spaces. The booth and the library both scaffold the experience, transforming something threatening into an experience that appears appealing and safe.

In contrast, consider British artist Jeremy Deller’s open-ended dialogue program, It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq, which traveled to several museums in the US in 2009. The piece featured two guests, an Iraqi translator and a US Army reservist, who sat on couches in a conversational space, flankedby a powerful artifact—a car that was destroyed in a suicide bomb attack in Baghdad. The goal was to support “messy, open-ended discussion,” and the draw was the idea that visitors could go to the museum and talk about Iraq with someone who had actually been there during the war.

I saw It Is What It Is twice at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Both times, the central square it was situated in was crowded with people enjoying art, hanging out with friends, and working. I never saw anyone engage in dialogue with the guest experts. Even with a couple of comfortable couches, a provocative object, and a sign that said, “Talk to X from 3-5,” the barriers to participation were high. From my perspective, It Is What It Is was not designed with sufficient scaffolding to robustly and consistently support dialogue. It didn’t bridge the social barriers that keep people from naturally talking to strangers. It didn’t set expectations for what would happen (which was intentional) and that made people more wary about getting involved. Whereas both the Human Library and the advice booth were audience-centric, focusing on what visitors wanted to discuss or ask, I felt like It Is What It Is was trying to push something at me. It felt like if I sat on that couch, someone might talk at me or try to sell me their view.

By formally linking individual entry points to a social experience, the Human Library and the Advice booth successfully engaged a stream of diverse users. While the experiences were structured by the platforms, they often evolved into the kind of “messy, open-ended” dialogue that Jeremy Deller sought with It Is What It Is. But without designed infrastructure for engagement, the results appeared more haphazard. It Is What It Is was an unscaffolded social platform, one in which the connection between individual actions and the shared outcome was not well defined. In open-ended platforms, interesting and surprising social interactions may occur. But they are more likely to occur consistently in well-structured ones.

Platforms and Values

Social platforms need to be well designed to be successful, but that doesn’t mean you need to entirely redevelop your institution to make every visitor experience fit into a structured framework. Designing an entire institution that functions like a Human Library or an advice booth probably isn’t your goal. Your goal is more likely to promote social learning, creative participation, or meaningful conversations about institutional content. There are ways to achieve these goals with low-tech, socially networked platforms, many of which are just as effective as and more natural than their high-tech counterparts.

Designing the best social platform for your institution or project boils down to understanding your participatory goals. How do you want visitors to learn from or interact with each other? Do you want to promote dialogue, as the Human Library does? Do you want to promote group collaboration? Do you want visitors to respond to each other, to help each other, to create things together? If you think about network effects in terms of a useful outcome for visitors and institutions rather than in terms of data collection, you can design platforms that reflect your participatory values.

Let’s look at three examples of institutions that created simple platforms for three very different participatory goals.

To encourage visitors to develop a stronger emotional connection to Worcester City Gallery and Museum’s collection, that institution created an exhibition called Top 40 in which visitors voted for their favorite paintings by paper ballot. Top 40 featured forty paintings from the permanent collection, each of which was labeled with a large number indicating its place in the Top 40 standings. The exhibition ran through the summer of 2009, and the labels were changed weekly to reflect the count from visitors’ ballots. Collections Manager Philippa Tinsley wrote:

Spontaneous discussions broke out in the gallery on the relative merits of different pictures; visitors of all ages came back again and again to see where their favourite was in the chart that week and to cast another vote—at times they were queuing outside before we opened. As well as our existing audience, new visitors came just because they wanted to be part of it.[14]

By developing a platform that was highly responsive to visitor input, the Worcester City Gallery and Museum achieved their goals to connect visitors to the paintings on display and the institution as a whole.

To promote collaboration among teenagers and young adults, the Ontario Science Centre uses front-line staff and labels in an atypical way in their Weston Family Innovation Centre (WFIC). Many exhibits in WFIC feature no instructional text or graphics, and visitors struggle to figure out how to use them. WFIC staff known as “hosts” mill around engaging visitors casually and socially. When a visitor approaches a host with a question about how something works or what it’s for, the host will often pull in another visitor, saying, “Hey, can you help us out? We have a question.” The hosts thus link visitors—often strangers—to each other, and provide a supportive environment for those visitors to play and learn together. There are some visitors for whom this strategy would be very off-putting, but it fits in with the overall vibe of WFIC and supports its goals for visitor collaboration.

To help visitors connect personally to a formal institution, in 2009 the Dutch ceramics museum Princessehof hosted a seven-month visitor co-created exhibition of wedding china called Shards & Happiness (Scherven & Geluk). The museum invited people from throughout the Netherlands to showcase their wedding china, wedding photos, and celebratory stories at the museum. These diverse personal stories prompted heightened levels of dialogue among visitors about their own family celebrations, and Princessehof engaged in extensive onsite and online programming to promote community conversations and sharing of wedding- and wedding china-related experiences. Staff even hosted a “wedding for a day” event in which visitors could pair off, walk down the aisle, and toss the bouquet just for fun.[15]

Each of these is an example of how an institution designed a platform to translate individual actions into collective benefit. Each of these projects “got better the more people used it.” And most importantly, each platform reflected the specific values and goals of the project at hand.

Designing Social Platforms for Specific Values

To design a platform that will reflect the specific values of an institution or project, consider these three questions:

- What individual actions will be available to visitors?

- What will staff do with the individual actions, i.e. how will the institution respond to them, incorporate them, and use them?

- How will the institution display the collective outcome of the individual actions?

Let’s look at each of these questions through the lens of a common museum platform: the comment board. While they seem simple, comment boards can be designed in very different ways to achieve different social results.

The individual action:

Comment boards offer visitors specific materials to use to share their thoughts. Different comment board designs bias people toward different results.[16] Sticky notes and pencils signal an easy, quick activity that anyone can do. A typewriter, or fancy markers and drawing paper, signal a more involved activity. In the Advice exhibition at the University of Washington, the staff provided visitors both with sticky notes to answer each other’s questions and a “bathroom wall” where they could scrawl whatever they wanted. While no one specifically told visitors, “you can write bad words on the bathroom wall but don’t do it with the sticky notes,” they certainly interpreted the interfaces that way.

The response:

Once visitors write their comments, what happens next? Can they immediately stick them on the wall, or do they drop them in a slot for some kind of staff processing? On some comment boards, staff curate submitted comments and pick a selected few to display for all to see. On others, visitors can place their comments wherever they like, even layering over each other’s.

Sometimes the staff is under responsive; visitors place their comments in the box and they languish there for weeks. Other times, staff members respond directly to commenters. When the National Library of Scotland put out a Victorian writing desk for visitors during an exhibition of famous authors’ letters to publisher John Murray, librarians committed to responding to letters that visitors wrote. They were shocked to find themselves quickly overloaded with multi-page, personal letters written in longhand to long-dead authors. Fortunately, the staff honored the promise—but they also learned to think more carefully about how they would respond to visitors’ contributions in the future.

The display:

Museums tend to use one of two types of platforms for display of visitor-generated content: those that value recency or those that value quality (or a mixture of both). Platforms that value recency put the newest visitor comments front and center, and previous comments are either archived or accessible on secondary layers. Platforms that value quality use some curation system (almost always staff led) to select featured content for presentation to visitors. Recency models may encourage more visitors to contribute because they will receive the immediate satisfaction of seeing their comments on display. In contrast, quality models may motivate less contribution, but those who choose to comment may be more invested in what they share.

Moving Beyond Recency and Quality-based Systems

There is a conflict between recency and quality-based models for showcasing visitor-created content. Recency models let everything through instantly, drowning out the gems. In contrast, quality models require staff time to read, curate, and post the best submissions. This can lead to exhibits piled with contributions languishing for weeks until the staff member in change can sort through them and select the best for display. How could these two models be usefully blended to improve the display on comment boards?

There’s no reason that staff members need to do the work of curating visitor-created content alone. As noted in the first chapter, there are many more people who enjoy spectating and critiquing content than there are those who enjoy creating it. Inviting visitors to sort and rate visitor-generated content takes the load off of staff members who rarely have the time to do it. It also provides “critical” visitors with an activity that generates useful collective outcomes from their frustration at poor contributions and delight at quality ones. Curating visitor-generated content is not only about expressing likes and dislikes; it’s a useful cognitive activity that promotes learning how to make judgments and connections among content sources. There are many historians, curators, and scientists who spend more time evaluating and analyzing content than generating it. Why not promote a participatory activity that reflects these important learning skills?

By incorporating the networked preferences of visitors over time, a visitor-generated exhibit could dynamically provide higher-quality offerings to spectators. But with this potential comes a worry that visitors will just select the funniest items, or the ones made by their friends, or will generally use criteria that is not in line with museum values.

The best way to address these concerns is by being explicit. If you want to encourage people to curate using particular criteria, give them the criteria. Say, “pick the photos you think best represent the theme,” or “pick the comments that are most provocative.” Or, you can say, “use your judgment and select the ones you think have the most value.” Clear criteria can help reinforce your goals, but they aren’t always necessary. Sometimes trusting visitors as participants means accepting that their values are just as valid as those of the staff.

Creative Approaches to Platform Design

With some creative thinking, it is possible to design platforms to meet even the most ambitious goals. In the simple example of sharing visitor-generated content, there are many other values beyond recency and quality that can be emphasized. Let’s take a look at how the same system could evoke two different values: diversity and reflective discourse.

Imagine a video kiosk in a history museum intended to invite visitors to “share your story” related to a historic event on display. A platform that values diverse sharing might employ kiosks that use different questions and themes to solicit different perspectives on the same experience. Visitors acting as critics might be asked to sort the videos into different perspective categories rather than rate them or pick their favorites. At another station, critics might be able to then select favorites within each category. In this scenario, spectators would not just see “the best” videos overall, but the best videos reflecting a diversity of perspectives.

Now imagine the same exhibit with a different platform that values reflective discourse. This exhibit might use heavier consistent theming across the video creation kiosks. Visitors might be prompted to select another visitor’s video as a starting point and make a video in response to it rather than reacting to an institutionally-provided query. For critics, the system would focus on commenting rather than rating or sorting. Videos might be featured based on the chain of response they generate rather than on the diversity of perspectives represented. In this scenario, spectators would see long multi-vocal dialogues played out across videos and text comments.

Two platforms, two designs, two different goals and desired visitor experiences. Let’s leave the world of the theoretical video kiosk and take a look at two real platforms—Signtific and Click!—that were successfully designed to reflect distinct values.

CASE STUDY: Structured Dialogue in the Signtific Game

Signtific was an online game platform that promoted dialogic discourse about wild ideas. The Institute for the Future released Signtific in 2009 to help regular people engage in futurecasting, or predicting the future. Signtific was not a museum project, but it could easily be adapted to cultural institutions as a low-tech internal or public brainstorming tool. It was, quite simply, a comment board that encouraged people to engage in dialogue with each other.

Here’s how it worked. The staff produced a short video introducing a provocative yet possible future scenario in the year 2019. In the first version of the game, the question was: “What will you do when space is as cheap and accessible as the Web is today?” The video explained: “In 2019, cubesats—space satellites smaller than a shoebox—have become very cheap and very popular. For $100, anyone can put a customized personal satellite into low-earth orbit.” It then posed the simple question: “How will the world be different?”

People were not allowed to answer the question generically. They had to pose their answer either in terms of “positive imagination,” (i.e. the best thing that could happen) or “dark imagination,” (the worst that could happen). Answers had to be brief—140 characters or less—and were displayed to look like index cards. Game designer Jane McGonigal called Signtific a platform for “micro-forecasting,” explaining “the idea was to make it easier for people to share small, quick ideas about the future.”

Spectators could very quickly scan the cards to see both the positive and dark answers and could click on any card of interest to follow up with a response. Players could not respond freely to each other but were required to use one of four types of response: momentum, antagonism, adaptation, or investigation. Players used momentum cards to add additional ideas, antagonism cards to raise disagreements, adaptation cards to suggest other potential manifestations of the same idea, and investigation cards to ask questions. The response cards were also limited to 140 characters.

Multiple response cards could be played on any other card, generating expanding trees of debate and discourse. The result was a network diagram of cards, a threaded dialogue that took place across many nodes. The game masters curated some of the most interesting cards daily and offered frequent rewards for “outlier” ideas that were improbable but fascinating.

A "positive imagination" card that spawned multiple response cards below.

Signtific provided a very deliberate framework to prioritize collaborative brainstorming about the future. These four design decisions reinforced their goals:

- Responses were kept short. This allowed people to scan many cards quickly and focus on responding to the most interesting ideas rather than wading through or generating long personal manifestos. It also made it easy to contribute quickly. Instead of focusing on crafting perfectly-written responses, players focused on the arguments they wanted to make and the cards that represented their interests.

- The scoring emphasized interpersonal play, not just solo participation. Players were rewarded with points for playing their own cards as well as for motivating others to contribute response cards. Players earned more points for starting a great discussion among many people than for personal pontification.

-

A Signtific user profile. The bar graph illustrates how many cards of different kinds the player has employed.

The profile setup encouraged people to experiment with different forms of argumentation. Each player’s personal profile tracked the number of each type of cards played and a small message read, “Are you stronger in some areas than others? Play another card to balance your strengths.” This simple message set an expectation for players to explore the different types of argumentation rather than sticking with the ones that were easiest for them to use.

- The “outlier” awards put wild ideas front and center. The scoring system rewarded people with special badges for suggesting ideas that were “super interesting.” One of the important techniques of futurecasting is to deliberately seek out aberrant possibilities. Since these more unusual cards were not necessarily going to receive special attention in the flow of the game, staff made sure to feature them wherever possible to encourage people to take risks and think broadly.

Signtific was not an open mushy conversation about the future. It was a structured platform of specific interactions guided by clear values of collaborative discourse and imagining multiple outcomes for a potential scenario. It was a well-designed platform imbued with the Institute for the Future’s value on “helping people make better, more informed decisions about the future.”

Many civic and cultural institutions share this goal, and the Signtific platform could be adapted to both professional strategic brainstorming and crowdsourced dialogue about community issues. While Signtific’s online platform made it easy to scale the number of cards played, this could easily be designed as a physical game played with colored sticky notes. Imagine offering a set of bins with different colored stickies—red for momentum, green for antagonism, blue for adaptation, and so on. Rather than inviting visitors to just share their response to an institutionally provided prompt, a Signtific-like platform could encourage visitors to collaboratively address tough scenarios like the future of transportation, multi-lingual education systems, or genetic modification of humans.[17]

CASE STUDY: Testing the Wisdom of Crowds at the Brooklyn Museum

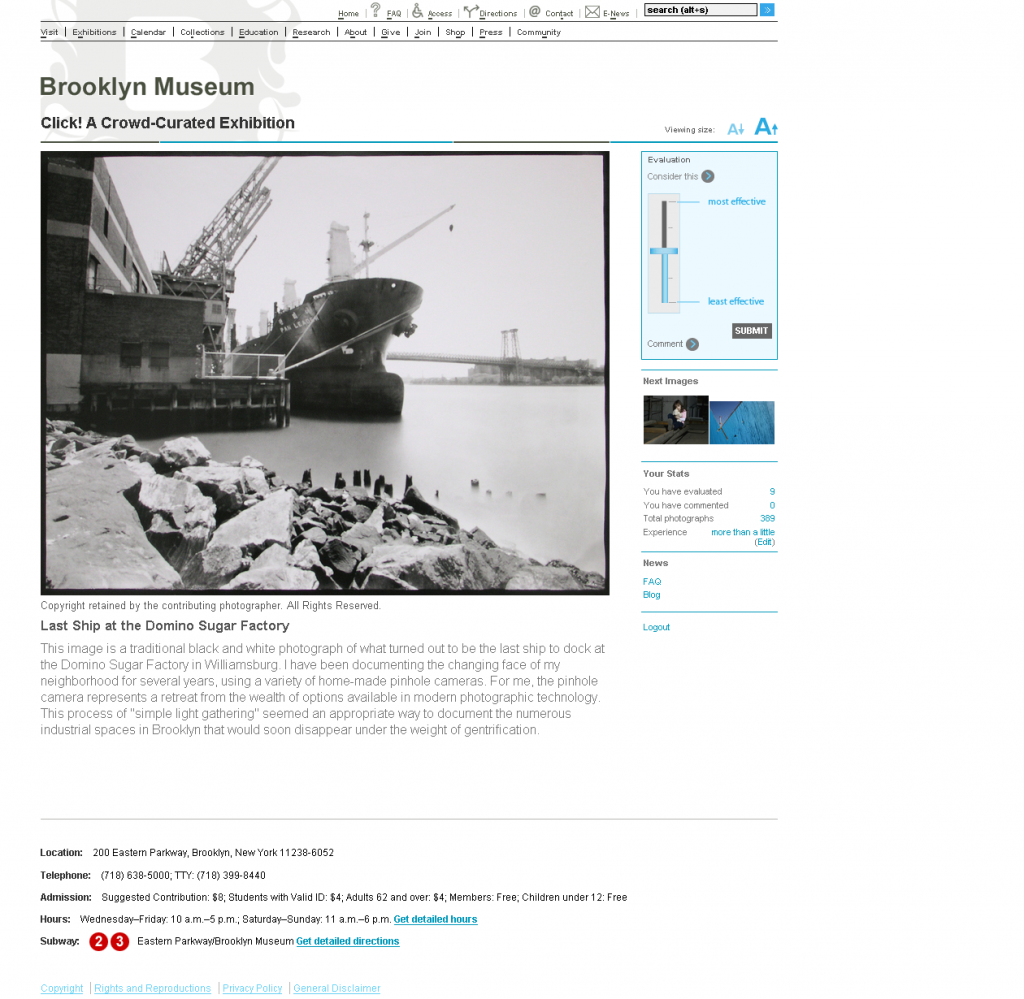

When it comes to cultural institutions taking an ambitious, creative approach to designing a platform with specific values, Click! takes the cake. Click! A Crowd-Curated Exhibition was developed in 2008 by the Brooklyn Museum to investigate the question of whether crowds could “wisely” judge something as subjective as art.[18] Click! happened in three stages: an open call for submissions, online judging of entries, and presentation of the final exhibition. In the open call, people submitted photographs on the theme of “the changing face of Brooklyn.” Then, the museum opened an online tool where visitors could judge the photographs on their artistic quality and relevance to the exhibition theme. Finally, staff mounted an exhibition of the photographs with prints scaled in size to match their rank in the judging scheme. The photographs were also displayed online, where visitors could access more information about each photo and how it was judged.

The submission process for Click! was fairly standard, but the judging and display were highly unorthodox. Despite the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive forays into social media, the team designed the judging platform to intentionally limit the social nature of the experience. Citizen curators made their judgments privately. They could not see cumulative scores for each photo nor the comments others had made. They couldn’t skip photos or pick the ones they wanted to judge. They couldn’t send links to friends to encourage them to vote for their favorites.

Why did the Brooklyn Museum team deliberately restrict social behaviors? In simple terms, they wanted to build a fair platform to test the wisdom of the crowd. According to social scientist James Surowiecki, crowds are only “wise” if individuals cannot have undue influence on each other. If everyone guesses the number of jellybeans in a jar privately, the average will come very close to the true number. But if everyone shares their guesses, or encourages their friends to guess like them, the average will not be as accurate.

Restricting social behaviors also helped demonstrate respect for the artworks. It helped judges focus on the photographs, not discussion surrounding them. For the same reason, judges moved a bar on a sliding scale to judge each photograph rather than picking “best out of five” or assigning a number to each image. The team felt that a subjective rather than numerical assessment reduced the emphasis on the “score” for each image.

The Click! judging interface. Citizen-curators used a sliding scale (top right) to judge each photograph for its artistic quality and relevance to the theme. They could also leave comments, but these would not be revealed until judging was complete. Instead of social content, the judging platform provided personal statistics (bottom right) to encourage judges to continue their work.

The platform also required judges to create profiles with just two data points: geographic location and self-reported art knowledge. The team used these data points later to run comparisons so they could see if self-described experts rated photos differently than their novice counterparts, or whether Brooklyn denizens had different perspectives on the “changing face of Brooklyn” than judges in other areas.

In the end, the photos were displayed, both virtually and physically, sized relative to their rank in the judging scheme. The physical display was not thematic; it was entirely random. In the physical exhibition, the sizes of the prints were fixed, but on the Web, audience members were able to resize the photos contextually by changing data criteria, looking at the photos resized based on geographic location or self-reported art knowledge of judges. Interestingly, the top ten photos selected by judges of all levels of self-reported art knowledge included eight of the same images, suggesting that “crowds” of people with little art knowledge are likely to make comparable choices to those made by experts.

Click! spurred conversation among participants and cultural professionals not just about the photographs’ value, but also about the ways cultural institutions might appropriately engage the public as participants. Once mounted, the exhibition was a highly social space. The community of people who had been involved in making it—photographers and judges alike—came to share the experience with each other and with their own networks.

Online, the conversation continued.[19] Users continued to make new comments post-opening, energized by the seeded content from the judging phase. Visitors could surf the images that were “most discussed,” which promoted ongoing dialogue around the photographs. The online platform also allowed visitors to compare the relative ratings of different photographs—a flexible opportunity for visitors to practice juxtaposition on their own. Visitors could even view photographs that enjoyed the greatest “divergence of opinion” among the different self-defined geographic and art expertise groups. This prompted yet another discussion about the relative abilities and prejudices of different groups of people in determining the aesthetic value and relevance of images to a broad public.

Click! was a controversial experiment because its value system was so different from that of traditional art institutions (including the Brooklyn Museum itself). Its goal was not to find and display the best photos submitted by photographers. Instead, the goal was to perform a public research project about crowd-based decision-making. As Shelley Bernstein, organizer of the show, put it, “it’s a conceptual idea put on the wall.”

Conceptual ideas don’t necessarily make pretty exhibits in a traditional sense. The Museum’s contemporary art curator Eugenie Tsai commented that, “[Click!]’s about data, and making the data visual. It’s not really a photography show in the way I would curate a photography show.”[20] Bernstein and Tsai were both explicit about the fact that they made decisions in favor of research and against the most beautiful exposition of the art. All the photos were printed with the same process, and their sizes were determined by the judging process rather than aesthetic preferences. Critics from the New York Times and the Washington Post commented that the resulting show was not that visually impressive, but they were comparing Click! to photo exhibitions, which Bernstein would deem inappropriate. It would be more correct to compare it to data visualizations like tag clouds or spark charts—whether the audience wanted that or not.

Click! was a deliberate attempt by a museum to test something and present the results, saying, “don’t judge this as art.” Not everybody believes or wants to hear that. Some of the photographers who submitted their work to Click! were not thrilled to learn that they would not be able to control the way their photos would be printed, and some were skeptical about the validity of the public curation platform. As one photographer put it, “Why it is better for the crowd to use this peculiar (annoying and frustrating) method, is beyond me.”[21] To some, the collaboration was a force fit to institutional goals. Fortunately, according to Bernstein, her team’s open and clear communication with the artists about the project helped keep most participants feeling positive.

Some participants didn’t care if their work was being exhibited as data; they were just thrilled to see their photographs up in the museum. This feeling of connection extended to those who had served as online curators as well. As participant Amy Dreher put it: “I felt ownership over what was on those walls because I had been involved in it from the first walk we took to the last photo I ranked.”[22]

Click! may have generated dynamic tension between what the museum wanted to present and what some participants and reporters wanted to experience, but the institutional team stood by their initial goals as a valuable experiment and visitors responded positively to the exhibition. Ultimately, experimenting with the questions of how visitors might be engaged in curatorial process and whether crowds of visitors could be “wise” evaluators of art were the most important parts of the Click! experience from the institutional perspective. The exhibition was just an output of that research.

Platforms and Power

Click! was controversial because it threatened the traditional power relationships in a cultural institution between visitors and staff, experts and amateurs. Socially networked platforms have political implications. If experts, exhibits, and program staff no longer deliver content exclusively but also serve as facilitators connecting one visitor’s experience to another’s, institutions’ roles as content authorities change. This is threatening to the power that staff members have enjoyed for many years in cultural institutions, and it can generate a great deal of fear and resistance.

These power struggles are not new, especially in the educational sector. In the 1960s and 1970s, educational revolutionaries like Paulo Friere and Ivan Illich spoke out against traditional schooling systems, claiming schools were oppressive systems promoting non-reciprocal relationships between teachers and students. Friere and Illich both sought alternatives that would engage equitable communities of learners, and one of the ideas Illich promoted was networked education via what he called “learning webs.” In his 1971 manifesto, Deschooling Society, Illich suggested an educational model based on a person-to-person network in which each individual would list his skills in a kind of phonebook.[23] The phonebook would serve as the “available curriculum,” and people could call or write to each other and solicit instruction from each other on everything from auto mechanics to poetry. Illich argued that this kind of citizen-powered education would be much more powerful and valuable to communities than formal schools.

What Illich didn’t discuss was exactly how he would design his hypothetical phone book. As we’ve seen in the above case studies, there are significant value judgments inherent in the design of participatory platforms. How would you design Illich’s educational phone book? Would you organize it by skill offered, location of the instructor, or the name of the person offering it? Would you include information about each person’s relevant experience and credentials? Would you encourage learners to rate their learning experiences and use those ratings to reorder the list? Would you introduce a feedback loop to help people find the most popular teachers, or would you design the platform to distribute learning experiences as equitably as possible across participants?[24]

Each of these decisions would send the resulting community experience down a different path. Platform designers have incredible power over the user experience, but it’s a kind of power that may be unfamiliar to those accustomed to designing and presenting content experiences. It’s not the power to be the only voice in the room but the power to determine who speaks and in what order.

To be successful leaders in a socially networked world, cultural institutions must feel comfortable managing platforms as well as providing content. One of the primary fears museum professionals (and all professionals) have about entering new relationships with audiences is the fear of losing control. However, in most cultural institutions, the professional expertise of the staff—to preserve objects, to design exhibits, to deliver programs—is not based on content control. It’s based on expert creation and delivery of experiences. Expertise is valuable, even in a platform-based institution. The problem arises when expertise creates a feeling of entitlement to control the entire visitor experience. Power is attractive. Being in control is pleasant. It lets you be the only expert with a voice. But if your expertise is real, then you don’t need to rule content messages with an iron fist. You can manage the phone book instead of directing the classroom.

Developing platforms to harness, prioritize, and present a diversity of voices around content does not mean giving all the power to visitors. Platform designers grant users a few specific, designed opportunities—to create their own content, to prioritize the messages that resonate best for them personally—in the context of a larger overall ecosystem. The platform is what’s important. It’s a framework that cultural institutions can (and should) control, and there’s power in platform management.

Platform managers have four main powers—the power to:

- Define the types of interaction available to users

- Set the rules of behavior

- Preserve and exploit user-generated content

- Promote and feature preferred content

These powers constitute a set of controls that constitutes a real and valuable authority. Let’s take a look at each one and how it applies in cultural institutions.

The power to define available interactions:

This power is so basic that it is often overlooked. On YouTube, users share videos. In Free2Choose, visitors vote on questions of personal freedoms. In the Human Library, people have one-on-one conversations. On Signtific, players debate the future of science. Every platform has a limited feature set and focuses on one or two basic actions that users can take. Cultural institutions don’t need to offer every kind of interaction under the sun—they just have to pick the few interactions that most support the kind of behavior and content creation that they value. There’s power in the specific decisions about whether users will be allowed to contact each other directly, make comments or ratings, or produce various kinds of digital and physical artifacts. When staff members focus the platform on a very small set of active features, they are able to steer the direction of the overall user experience and the body of growing visitor-driven content.

The power to set the rules of behavior:

Online participatory platforms influence user and community behavior both implicitly through the tools that are and aren’t offered and explicitly through community management. Every online social network has rules about acceptable content and ways that users can engage with each other, and those rules have serious implications about the overall tone of interaction on the site.

Most cultural institutions tend to rely on implicit rules of behavior, but it’s a good idea to draft community guidelines or information about what is expected from visitors in a participatory environment. For example, the Make History story-sharing site for the National September 11th Memorial and Museum informs users that they should only share their personal experience of September 11th and should do so as accurately and honestly as possible. The community guidelines also note: “Given the intensity of the event, some strong language may be appropriate in certain stories. But consider that this site will be used by people of all ages.” The staff set guidelines that honored the emotional nature of September 11th memories while encouraging users not to go overboard.[25]

Differences in community guidelines and rules also often influence the makeup of users who feel welcome and choose to participate. When it comes to cultural institutions, it’s important to make sure that staff members’ own personal biases toward certain kinds of behavior don’t overly dictate who feels comfortable participating. If you have some particular audiences in mind for a project, involve them in deciding what constitutes inappropriate behavior. A platform for parents might have very different community guidelines than one for artists or another for young historians.

The power to use and exploit user-generated content:

Platforms have the power to set rules related to preservation and ownership of the content they display—often with quite strict intellectual property statutes that favor the platform over users. Every time someone posts a video on YouTube, she gives the site the right to use that video in perpetuity however it sees fit. She owns the content, but she grants YouTube:

A worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, sublicenseable and transferable license to use, reproduce, distribute, prepare derivative works of, display, and perform the User Submissions in connection with the YouTube Website and YouTube’s (and its successors’ and affiliates’) business, including without limitation for promoting and redistributing part or all of the YouTube Website (and derivative works thereof) in any media formats and through any media channels.[26]

This is a standard clause in the Terms of Service of many online social platforms.

Cultural institutions have different standards for managing intellectual property, protecting visitors’ privacy, and monetizing visitors’ creations. While museums tend to be more protective of their own and their lenders’ intellectual property than online social platforms, they are also typically more protective of visitors’ rights to control what they make and do. For example, when the Denver Art Museum invited visitors to make their own rock music posters in the Side Trip exhibition, staff didn’t automatically display copies of each poster on the wall. They asked visitors whether or not they wanted to share their posters publicly.[27]

There are many models for how to share and use visitor-generated content that respect both institutional and visitors’ interests. Here are a few examples:

- The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Ghosts of a Chance game accessioned player-generated objects into a temporary part of their collection database, with clear rules about what happened to the objects at the end of the game (they became the responsibility of the game designers, a sub-contractor to the museum).

- The Metropolitan Museum used visitor-generated photos from Flickr in the popular “It’s Time We Met” advertising campaign, following user-specific licensing requirements to credit visitors properly.[28]

- The Chicago Children’s Museum used visitor-generated multimedia stories in their Skyscraper Challenge exhibit (see Chapter 2) as the basis for research on cognitive development.

- The Powerhouse Museum and the Brooklyn Museum have both created print-on-demand books of content generated by visitors involved in community exhibits and online projects.

- At the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, Gail Durbin has discussed using content created in museums as the basis for customized on-demand retail items, like personalized calendars showing images of your favorite exhibits, or one-off books of images captured at a fabric-making workshop.

In the same way that Web 2.0 sites display a range of respect for user-retained intellectual property, cultural institutions can navigate and create their own rules—with related powers—for content developed by visitors.

The power to promote and feature preferred content:

One of the greatest powers retained by participatory platform managers is the power to feature content that reflects the values of the platform. Just as the question of which stories to feature and bury in a newspaper is a question of power, so too is the question of how to feature content in social networks. Recall the alternative strategies for how to feature content on comment boards; these strategies are fundamentally about the question of how content will be selected for promotion. Institutions may promote the most popular content, the newest content, staff-selected content, or content that is unique in some way. While some platform designers strive for transparency in promotion systems, most tailor their systems to feature the kind of content and behavior that they want to see modeled for other users.

There was a fascinating example of the power of platform design in the successive redesigns of Facebook from mid-2008 to mid-2009. Over that year, Facebook evolved from focusing on personal profiles shared with small groups of known individuals to focusing on publishing lifestream-style feeds of status updates and short-format content for mass audiences. Whereas previously Facebook was a place to maintain a profile and connect to a web of friends and acquaintances, by the fall of 2009 it had become a personally relevant content stream, a dynamic newspaper created for each user (and shared with the rest of the world by default). Some users complained and left the service, but most remained—and changed their own behavior to match Facebook’s new design.

The power to promote and organize users’ content may be the most important platform power for cultural institutions because it is the one that most dramatically enables the platform to present its values and model preferred behavior. It is also the most technical power, because it requires understanding how design decisions affect broad patterns of user behavior.

Cultural institutions are still learning to wield this power effectively. When museums do assume this power, it is often in a zero-transparency way that doesn’t model behavior for users. Visitors are invited to contribute creative work or data, and then must wait until the end of a contest or submission period to see what the staff selected to feature. In opaque systems, visitors can’t adapt their contributions based on staff feedback along the way. Compare this to the Worcester City Gallery and Museum’s Top 40 exhibition in which visitors could access new information about the relative rankings of paintings on display every week. In Top 40, the regular refreshment of featured content motivated people to keep visiting and participating throughout the run of the exhibition.

There are real opportunities in a participatory world for cultural institutions to retain authority related to visitor values, experiences, and community behavior. The power of the platform may not let the staff dictate every message that floats through the doors of the institution. But with good, thoughtful design, it can ensure that those messages enhance the overall visitor experience. When you are able to network individual visitors’ experiences in ways that are both useful and beautiful, you will motivate new experiences and relationships that are exciting and valuable for the institution and users alike.

***

This chapter focused on designing platforms for connections among people in cultural institutions. This leads to an obvious and uneasy question for museum professionals: what about the objects? If institutions evolve to support visitors creating, sharing, and learning from each other, where does the collection fit in? Chapter 4 addresses the unique role of objects in participatory institutions. Artifacts can be the heart of platform-based experiences, the “object” of visitors’ conversations and creative expression.

Chapter 3 Notes

[2]Near is still open at the New York Hall of Science as of this printing.

[3] This is effectively the same as the scheme for A Matter of Faith at Stapferhaus Lenzbergon page 85, but with a less confrontational question and a simpler interface.

[4]Free2Choose is open as of this printing with no scheduled end date.

[5] Sue Allen and Josh Gutwill’s excellent article, “Designing Science Museum Exhibits with Multiple Interactive Features: Five Common Pitfalls,” appeared in Curator, issue 47, no. 2 (2004) and is available for download here [PDF].

[6] Play Just Letters.

[7] From the institutional perspective, the mediating technology let people cross too many social barriers.

[8] Until 2010, this project was called Living Library. It was renamed Human Library due to a legal conflict. I have changed all references to Human Library for clarity, but some of the referenced downloads may include the old term.

[9] Download the comprehensive Human Library Organizer’s Guide, which is available in eight languages here.

[11] Download the complete evaluation report from the Turkish Human Library here [DOC].

[12] This excerpt came from the Human Library Organizer’s Guide referenced above. For more reflections from Books, check out this page.

[13] There is a longer case study about Advice in Chapter 3.

[14] Read Tinsley’s complete account in a Nov 2009 blog post, Guest Post: Top 40 Countdown at the Worcester City Museum.

[16] For a detailed account of how different comment board prompts and materials affect visitor behavior, consult pages 16-22 of the formative evaluation of the nano exhibition at LACMA Lab, available for download here [PDF].

[17] At the 2009 Museums in Conversation conference in Tarrytown, NY, Elizabeth Merritt tested this out during a lunch session about the future of museums. Colleagues from museums around New York state were quickly able to imagine some positive and dark futures for museums—and to adapt and investigate them in some funny and surprising ways.

[18]Click! was inspired by The Wisdom of Crowds, a 2004 book by social scientist James Surowiecki, which argued that large groups of non-experts can be collectively “wise” when individuals in the group are able to make decisions without overly influencing each other’s choices.

[19] Explore Click! online.

[20] Listen to a one-hour panel discussion about Click! with Tsai, Bernstein, and technologist Jeff Howe here.

[21] See comment #27 on Shelley Bernstein’s June 2008 blog post, Preparing to Click.

[22] Dreher described her multi-faceted involvement in Click!, which started with exploratory walks with fellow photographers, in “The Click! Experience: A Participant’s View,” in Exhibitionist, 28, no. 2 (2009): 55–58.

[23] See Chapter 6, Illich, Deschooling Society (1971), especially the section on “peer-matching networks.”

[24] For one interesting approach to networked learning, check out The Public School.

[26] Read the complete Terms of Service for YouTube.

[27] Denver Art Museum educators did, however, archive a copy of every poster made for internal evaluation and collection purposes.