Hosted projects, in which the institution turns over a gallery or a program to community partners, are common vehicles for visitor participation. Hosting happens frequently in the context of formal partnerships: institutions regularly host traveling exhibits, artists-in-residence, independent tour operators, and special functions. This chapter does not focus on these formal relationships with vetted professionals but rather on situations where the institution is used or repurposed by amateur groups and casual visitors.

There are four broad reasons that institutions may choose to pursue hosting models for participation:

- To encourage the public to be comfortable using the institution for a wide range of reasons

- To encourage visitors to creatively adapt and use the institution and its content

- To provide a space for diverse perspectives, exhibits, and performances that staff members are unable or unwilling to present

- To attract new audiences who may not see the institution as a place for their own interests

Unlike other participatory models, in which the institution needs to somehow motivate and convince visitors to participate, hosting requires no coercion—just an open platform in which visitors can do what they like. But in most cases it’s not that simple. Complications arise when institutional and participant perspectives about what is valuable diverge. Hosting is only a useful technique when institutions have clear reasons why they want to provide a particular opportunity to visitors. In the same vein, when forbidding visitors to use the facility in certain ways (for example, to take photographs or to have loud conversations), staff should understand the potentially negative impact these limitations may have on visitors’ relationship with the institution.

Consider the concept of “loud hours.” Some museums and libraries have instituted loud hours to provide opportunities for visitors to talk more freely than they would at other times. Loud hours help some visitors feel more comfortable in cultural institutions by explicitly permitting them to communicate at the volume that is natural for them. In art museums, staff can use loud hours to encourage visitors to talk about the art, promoting social learning experiences that some visitors might feel uncomfortable engaging in under normal conditions.

Loud hours may be distracting and frustrating to patrons and staff members who value museums and libraries as quiet places. For an institution to confidently offer loud hours, staff members have to feel that the benefits outweigh the negatives. The institution needs to evaluate loud hours not just for the potential to generate noise, but also for the extent to which the program can support social learning and help engage new audiences. Loud hours might be more effective at promoting social engagement if the environment provides specific prompts for visitors to respond to and discuss. Loud hours might be most effective at attracting new audiences if offered at specific times of day or outside traditional open hours.

Hosting strategies can be used to implement simple programs, but they can also be used for institution-wide efforts. Hosting can be a strategic way to demonstrate an institution’s commitment to a particular topic or audience. By hosting a large-scale event or offering space to community partners from other organizations, cultural institutions can demonstrate their unique ability to serve as a “town squares” for public engagement.[1] When you can articulate the goals behind a hosting strategy, you will be more likely to design it in a way that best serves institutional goals and visitors’ needs.

Hosting to Promote Casual Use and Revenue Generation

Loud hours are an example of a hosting strategy that is focused primarily on encouraging visitors to feel at home in cultural institutions. Basic design considerations, such as the amount of comfortable seating, hours of availability, ticket prices, dining facilities, and services for guests with disabilities all impact the extent to which visitors feel comfortable and well-hosted in a cultural institution.

Most cultural institutions are comfortable hosting visitors for social experiences—for example, providing a nice setting for a date or a family outing. Many museums have started counting visits to gift shops and restaurants in their overall visitor counts, arguing that shoppers and café patrons are visitors even if they don’t attend exhibitions or programs. Similarly, many institutions aggressively market themselves as venues for special functions, weddings, and birthday parties. While most museums have some restrictions about who can rent the facility or for what purposes (for example, forbidding raves or political fundraisers), facility rental has become a significant way to cover operating costs. Hosting visitors for meals, functions, or gift-shop purchases is typically considered positive, since these activities generate revenue and connect the institution to visitors’ personal lives, however loosely.

When it comes to non-revenue-generating casual uses of cultural institutions, the situation can get complicated. Consider the question of providing free wireless access to the Web (Wi-Fi). Wi-Fi has become a core offering at libraries, where it helps fulfill institutional missions to provide citizens with open access to information. At museums, the question of whether to provide Wi-Fi is less clear. Some institutions see Wi-Fi as a basic provision that helps visitors learn in the museum with their own devices. Others want to encourage people to spend time in the museum casually, even if they are using the Web for uses unrelated to institutional content.

A banner outside the Indianapolis Museum of Art advertises Wi-Fi as one of the free amenities of the institution. Image courtesy Indianapolis Museum of Art.

The Wi-Fi debate is indicative of the cultural biases inherent in determining what makes an institution a good host. Suzanne Fischer, curator of technology at the Henry Ford Museum, has called Wi-Fi “a necessary service to visitors, like bathrooms.”[2] But the staff could just as easily argue that visitors have access to the Web elsewhere in their lives and do not need it at the museum. A subset of visitors may consider Wi-Fi to be a necessity, just as other visitors would consider strollers or vegetarian options in the cafeteria to be essential. When staff members decide which casual activities to encourage, they dictate what subsets of people will be most comfortable visiting the institution.

Hosting to Encourage Creative Adaptation

Some visitors use cultural institutions as settings for their own creative expression or social experiences. These can be positive learning experiences that produce useful and attractive outcomes that advertise the institution. But they can also generate outcomes that violate copyright or make staff members and other visitors uncomfortable. While it might be charming to see a pastor leading a tour of a natural history museum for congregants, the staff might be disturbed if he reinterprets the displays to put forward a creationist perspective.

Again, this comes back to the balancing act between institutional and participant needs. Participants who use institutions for their own creative purposes focus on serving themselves and their own constituencies, and have only secondary interest in the institution and its broader audiences. Hosted participants are likely to regard audiences very differently from the way the institution sees them, and those differences may be a delight (when they make new audiences comfortable in the venue) or a mess (when they alienate or confuse other visitors).

For example, the blog Jumping in Art Museums features photographs of people leaping in museum galleries.[3] Washington D.C.-based artist Alison Reimus started the blog to express her desire to “jump for joy” when engaging with art. Reimus encourages others to share their joy as well, and the blog features photos of art jumpers all over the world.

The audience for the Jumping in Art Museums blog includes other art enthusiasts who are probably frequent museum visitors. But not all people who come to museums expect to see people jumping, or want to jump themselves. Some visitors, like the blog’s followers, are probably delighted by the jumping. Some institutions, like the Belgian FotoMuseum, were so taken by the idea that the staff took professional shots of visitors jumping. But staff members and security guards at some other institutions have been annoyed or concerned by the actions of these jumpers.

When creative adaptation is mission-relevant, staff will often provide formal sanction and infrastructure to support it. For example, in 2009 staff members at SFMOMA noticed that some visitors like to sketch the art in the galleries. So, the staff started hosting informal sketching hours in the lobby. The staff didn’t provide drawing instruction or programmatic content, but they did provide approval and social support for sketching, explicitly welcoming and celebrating an activity they hoped to encourage.

To make reasonable decisions about what kind of creative activities are appropriate to host, staff members need to be able to separate their personal reactions and preferences from the needs of the institution and its visitors. It is reasonable for staff members to intervene if they think that participants are making an environment unfriendly to other audiences or unsafe for objects on display. But it is unreasonable to object to activities that staff members simply don’t like or are uncomfortable with because of their own cultural preferences.

When guidelines for behavior aren’t clear, it causes confusion and frustration for both visitors and staff. I once wandered through an art museum with my father and an audio recording device, intending to record our conversation for a podcast about how visitors talk about exhibits. We were interrupted immediately by a gallery attendant who asked us to stop but could not give us a reason why. We went to the main desk, where we inquired about the policy and were instructed to wait for a response from the Manager of Public Relations. Twenty minutes later, she told us that we could record ourselves, but we could not record any sounds emanating from the artworks (which might be copyrighted), nor could we interview other visitors (no reason given).

We felt that our desire to create an audio piece at the museum was unsupported, so we left. No wonder people apply the term “rogue” to podcasts and tours led by individuals who are not museum staff.[4] In many institutions, even if these activities are not explicitly against the rules, they violate unwritten rules about how visitors can and should use the facility.

Hosting Outside Program Offerings

Cultural institutions are often more comfortable with creative adaptation of their facilities and content when they partner directly with artists, local hobbyist groups, or other community partners to develop offerings that are relevant to the institutional mission. Some art or cultural institutions host craft sales in December to promote local artists while connecting to holiday shopping. The Boston Children’s Museum hosts a weekly farmer’s market, which reflects an institutional value around healthy eating.

These creative partnerships are most useful when outside participants can provide services or experiences that the institution is unable to offer itself. For example, a science museum might not have the resources to run its own citizen science projects but would be happy to provide space to support local amateur scientists who are looking for a home base for their experiments.

Art museums have moved aggressively into the hosted arena when it comes to educational programming. In Denver, San Francisco, and Seattle, among other cities, art museums host large-scale monthly parties geared towards young professionals, often featuring collaborative art-making activities that are run by outside groups. Such activities include communal knitting, social games, and screen-printing. The Denver Art Museum’s Untitled program also features “detours” led by non-art professionals—from Jungian psychologists to zookeepers—who share their observations and reactions to the art on display. The late-night Remix program at the Seattle Art Museum includes a similar tour component led by guest guides called “My Favorite Things.”

These programs frequently offer the same kinds of experiences provided by unsolicited creative adaptations, like rogue art museum podcasts, but they allow institutions to vet creative partners before the event. Soliciting visitors and outside artists directly can also increase participation. People are more likely to engage enthusiastically in creative reuse of cultural institutions when they are specifically invited and encouraged to do so.

Hosting New Audiences

Hosted participation can help institutions connect with people who don’t naturally see cultural institutions as relevant to their own lives and interests. For these audiences, hosted projects are most successful when they demonstrate the institution’s ability to add value to an activity these visitors already enjoy. For example, many museums host “lates” that attract young adults to dance, flirt, and party in the galleries. These events are intended to help new audiences see the museum as a fun venue for a social experience.

These kinds of programs can be controversial for the institution. Some traditionalists do not see the benefit of spending resources on programming that is radically different from their usual offerings. But just as multilingual labels help foreign visitors feel comfortable and confident in museum galleries, social events can help young adult audiences feel comfortable in the museum setting.

A similar argument can be made for a popular type of hosted program in public libraries: game nights. Many American libraries host game nights, geared toward kids and teens, in which visitors use library computers and gaming consoles to play multi-player online and digital games. During these programs, librarians encourage kids to use the library in non-traditional ways—playing games, running around, eating pizza, yelling. Librarian Toby Greenwalt hosted family game nights at his library in Skokie, Illinois in 2008 and set up feedback stations for kids to share their thoughts. Kids made comments like, “This night is the best night at the library ever. I had so much fun.” and “this place is AWESOME!!!!!!!!!”[5]

Is this hosted program mission-relevant, or does it give kids a false sense of what the library is about? The librarians who run these programs argue that gaming in the library is on-mission when it comes to institutional goals that address community outreach and engagement, as well as their commitment to providing access to media content. The Skokie Public Library’s vision statement reads:

Skokie Public Library is essential to a vibrant and diverse community where individuals of all ages and families freely engage in lifelong learning and discovery, and enjoyment of popular culture and the arts. Residents have many opportunities to become well-informed, with their intellectual freedom and privacy protected, to benefit from cultural diversity, and to actively participate in the life of the community.[6]

Game nights support the sense that the library is a vibrant community space dedicated to family discovery, enjoyment, and learning. From the perspective of the institutional vision, game nights are just as mission-relevant as other hosted programs, like classical music lunch hours or community group meetings.

Hosting new audiences in this way helps people understand how their identity goals might be fulfilled at the institution. When a library fulfills a kid’s goal to challenge herself and be social, she starts to see the library as a positive and useful place that she can contextualize into her recreational choices. She may begin to look more broadly at what else it offers. As librarian Marian Hose wrote about her own experience hosting a game night: “The kids had great fun and we saw plenty of fresh faces in the library. Anyone who did not have a library card already was signed up for one and many of the new kids have come back again the use the library ‘for real.’”[7]

Not all of the kids who come to game night (or to other hosted library programs) return to use the traditional resources and functions of the library. That’s fine. The Skokie Public Library’s vision statement doesn’t make any value judgments about the right kind of “lifelong learning and discovery” experiences for its patrons. If the staff members truly embody this vision, they can feel positively about patrons who only use the library for limited mission-related purposes—whether to play games, participate in meetings, or read.

The question of which hosted programs are worth pursuing becomes more complicated when hosted programs grow larger and more expensive. What’s the value of engaging new communities if it requires a lot of time and money? That’s the question the Ontario Science Centre grappled with in the next case study.

CASE STUDY: Assessing the Value of Hosting the 888 Toronto Meet-up

On August 8, 2008, the Ontario Science Centre (OSC) hosted a meet-up called 888 for international YouTube users. 888 was expensive to host, complex in its outcomes, and provoked many questions about the true value and cost of engaging new audiences.

888 emerged as an event idea from the OSC’s successful forays into online video sharing. The OSC had a high profile on YouTube and other video-sharing sites, and their videos—mostly short, staff-produced excerpts from demonstrations and outside speaker presentations—received millions of views on YouTube. The designer in charge of video production and sharing, Kathy Nicholaichuk, had become deeply involved with the YouTube community, and she expressed an interest in taking the OSC’s involvement further. She worked with staff members from the events, programs, and visitor experience teams to conceptualize a meet-up that would accomplish three goals:

- Demonstrate the OSC’s commitment to the YouTube community

- Bring creative, energetic, young videographers to the Science Centre

- Produce video content that would benefit the institution and the meet-up participants

Nicholaichuk and other YouTube enthusiasts promoted 888 via YouTube and other social media tools. Many YouTube users created videos in which they effused about the Ontario Science Centre before ever setting foot inside. About 460 people showed up for the actual event—the largest YouTube meet-up held to date. The event was a massive party in the Science Centre, featuring talent shows, open exhibit galleries, food and drink, and lots of cameras.

While participants came from all over the world, a survey conducted at the kickoff party indicated that more than 75 percent were local to Toronto or from Canada.[8] About half were under 19, and another quarter were 20 to 25 years old. More than one-third had never visited the OSC, and the majority attended with friends or family. Over 1,000 videos were made at the event, and the OSC received 2 million impressions from print, radio, and TV coverage. The videos themselves received millions of views and tens of thousands of comments on YouTube.

These numbers were impressive. The OSC has a commitment to promoting innovation, and like most science centers, it struggles to attract older teens and young adults (their core audiences are families and school-age audiences). As Associate Director of Daily Experience Operations Kevin Von Appen noted, “[Teens] explore technology and they innovate. Those are exactly the kind of skills, attitudes, and behaviors we’re trying to grow in our visitors.” 888 clearly portrayed the OSC to young adults, and their own social networks of friends and followers, as a cool place to hang out and an attractive context for social experiences.

The vast majority of videos made and shared from the meet-up were social in nature, focusing solely on participants’ excitement at meeting each other, partying, flirting, and hanging out. While many videos did feature or mention the OSC as the location for the social activity, there were only a handful of videos in which 888 participants actually used exhibits or tried to communicate about science in some way. Everyone had a good time and no one did anything offensive, but the activities shown in the videos are not representative of typical OSC visitor experiences, nor do they communicate the venue experience accurately to potential visitors. On one level, this is to be expected; the OSC hosted the YouTube community so it could have its own YouTube experience. But on another level it’s problematic because large numbers of YouTube spectators continue to be introduced online to the OSC as a venue for a party, not as an educational facility.

In other words, 460 young people produced 1,000 videos of themselves having a great time at the Science Centre. And the question remains: what is that worth?

From the participant perspective, the experience was incredibly valuable. Several participants made comments like, “The best time of my life!!… I will never forget it.” The meet-up was well designed to support YouTube users’ needs, and those users felt fully able to enjoy the venue for their own social and creative purposes.

From the institutional perspective, the results were mixed. The OSC spent about US $74 per participant (mostly on labor) to promote and host the event. The staff had hoped that more participants would use the meet-up as an opportunity to engage with the exhibits and produce videos reflecting experiences that were educational in nature. But the event also brought local young adults to the science center who otherwise weren’t visiting, and it may have encouraged some local YouTube users to see the OSC in a new light.

While the OSC team considered 888 to be a valuable experiment, they elected not to host an identical 999 meet-up in 2009. Von Appen commented:

Repeating it didn’t make sense as a next step. We had entered or engaged with something that was changing really quickly at the right moment in the right way, and we got the results we got. And now it’s time to be thoughtful about what comes next. We’re still looking for ways to make it easier, make it local, make it repeatable, make it deeper.

The 888 participants are the kinds of people that the OSC wants to attract through its innovation-focused exhibits and open-ended programs. Thus 888 was a starting point that established the Ontario Science Centre as a relevant and appealing venue for teen and young adult experiences. The question is how to transform a popular hosted event like this one into one that aligns more successfully with institutional goals.

Hosting as a Launch Point for Deeper Engagement

Events like 888 often feel discontinuous with the other programs cultural institutions offer. How can a successful hosted experience lead to broader engagement with institutional programs?

The first step is to be explicit about other programs that are relevant to participants’ interests. Only a small number of people who show up for a party or event will gravitate towards wandering through exhibits or picking up program brochures. It’s okay to offer participants at hosted events targeted activities that connect to other institutional offerings. The Denver Art Museum’s Untitled program isn’t just a party—the staff also provides activities that encourage participants to connect with the art in the galleries. Similarly, you could imagine a future YouTube meet-up at a science center or museum in which staff would provide specific challenges for participants to make videos related to the exhibits on display.

If your institution wants to engage hosted participants more deeply, start with an activity or experience that the audience already enjoys in your venue. If people use your museum as a place to take photos, ask if they’d consider playing paparazzi at an upcoming event. If they use your museum as a place to work, suggest a quiet spot or an exhibit that’s particularly good for inspiration. If they come with friends and give their own well-informed tours, invite them to volunteer as guides for school groups or other visitors. If they make out in a dark exhibit…well, some activities you might not want to encourage.

CASE STUDY: Hosting Teenagers at the Experience Music Project and Science Fiction Museum

In 2009, I started working with the Experience Music Project and Science Fiction Museum (EMPSFM) in Seattle on a project to enhance teen engagement with the museum. Like the Oakland Museum and the Days of the Dead (see page 298), EMPSFM has a flagship program that embodies the best of their engagement with teenage audiences. This program, called Sound Off!, is a battle of the bands for musicians aged 13 to 21. Each fall, youth bands submit applications, and twelve are selected to participate in a series of four semifinal concerts in the spring. These twelve bands receive mentoring from industry professionals, lots of press attention, and the opportunity to perform in front of hundreds of screaming fans at the museum.

In my first meeting with EMPSFM staff members, they commented that Sound Off! is an amazing program, but they felt the teens who participate and attend the semifinals only see the museum as a venue for a cool rock concert. They were concerned that teens didn’t see the museum as a place with other appealing or worthwhile experiences. The staff wanted to find ways to capitalize on teens’ love of Sound Off! to get them more engaged throughout the institution. This is a multi-year process with the goal to develop programs that are teen-led and which expand the museum’s teen audience beyond those who participate in Sound Off!

Rather than designing a new program and figuring out how to motivate teens to engage with it, we started with the teens who love Sound Off! and inferred other kinds of experiences that might appeal to them. Because these teens see the museum as the host of an enjoyable live music experience during Sound Off!, we decided to use their preexisting interest in live music performed by local bands as the starting point for other museum experiences. EMPSFM is engaging the Sound Off! audience more deeply with the institution in four ways:

- Online, staff members opened a social network where Sound Off! enthusiasts and bands can connect with each other and learn about other live music shows and venues in the Pacific Northwest. This online community attracts teen musicians and their fans, as well as young band managers and promoters who want to announce their gigs. We worked with teens who were already engaged with Sound Off! as youth advisory board members and former competitors to promote and produce content for the online community. The goal is that, over a three-year timeframe, the online community will transition from being managed by staff to being managed by youth advisory board members and Sound Off! participants.

- On the educational program side, the staff drew clearer lines among the different music-making and performance-oriented educational programs at the museum, so teens could more effectively pursue paths to and from the Sound Off! experience. The museum offers several educational programs, including camps and intensive workshops, to help young musicians improve their musical and performance skills. Many bands who enter the Sound Off! competition are unaware of these other opportunities. The vast majority of bands who enter the Sound Off! competition do not make it to the semifinals concerts, and they frequently end their participation with the museum for the year if they are not selected. The staff is working to explicitly advertise the opportunity for competitors to engage with courses and camps that may help them improve their chances in the competition for the following year.

- In the museum galleries, the staff is integrating multimedia content from Sound Off! semifinalists and winners into exhibitions, so that the bands’ fans can pursue their interest in these bands as part of a museum visit. The museum is integrating Sound Off! bands into pre-existing oral history projects and media exhibits focused on contemporary artists, and the staff are considering options that would allow teenage visitors to access and produce additional audio and visual content via mobile phone.

- Sound Off! itself is becoming more participatory. Over three years, audience members will gradually be invited to help judge the competition, to design T-shirts and graphics for the program, and to serve as journalists reporting on the entrants and the performances.

Hosting Exhibitions in Community Galleries

Not all hosted projects are event-based. One of the most frequent ways that cultural institutions invite people to share their own artworks, stories, and collections is through community galleries, in which individuals or community groups produce their own exhibitions. Unlike the Wing Luke Asian Museum’s co-creative exhibition development model (see page 286), community galleries are typically set up so that outside participants manage all aspects of content development, exhibit design, and fabrication themselves, within some broad guidelines set by the institution. Community members propose exhibitions in an application process, and the museum selects proposals to be implemented. The community members are responsible for developing and implementing their proposed exhibitions with minimal staff support.

Successful community gallery projects feature several logistical elements:

- The exhibitions are time-limited. A fixed term allows institutions to support many rotating voices while mitigating the adverse effects of a poorly executed community project.

- Participants receive a stipend for their work. This is usually a fixed amount for materials and development costs. If institutions want to engage less privileged community members, they may offer more significant compensation to cover time spent working on the project.

- Institutions provide basic schedules and frameworks for developing the exhibitions. Staff members typically meet with participants at fixed points in the process to respond to questions and help exhibitors stay on track.

- Beyond formal meetings, staff members are available to a limited extent to help participants with design and technical issues. Having an expert to talk with helps bolster participants’ confidence and develop their skills towards a higher-quality result. Unlike co-creative projects, in community gallery projects, the staff typically tries to limit—not extend—time consulting with participants.

- Participants are encouraged to develop marketing materials to promote their exhibits. This motivates participants to bring in their own audiences, who may be potentially new to the institution, rather than relying solely on the institution’s traditional visitors.

- Participants are encouraged to offer educational programs or tours during the run of their exhibit. Many community exhibits come to life when presented by the people who are passionate about the stories on display.

While community exhibitions often reflect topics of keen interest to niche audiences, the quality is not always at the level of the rest of the museum’s professionally produced exhibitions, nor are they likely to conform to institutional style guides. The results may appear inconsistent with other staff-managed galleries.

Community galleries are frequently designed to require as little staff involvement as possible, not to produce the best exhibitions possible. At the Detroit Historical Society, Director of Exhibitions and Programs Tracy Irwin has noted that while their community gallery allows the institution to reflect the unique and diverse stories of Detroit’s citizens, the quality of design varies widely. Graphic panels may be over laden with tiny text, or exhibitors may place objects and labels at heights that are not accessible to everyone. While the museum staff has the knowledge and experience to avoid dubious design choices in their own galleries, the community gallery is designed by partner groups, who have been given the freedom to design the exhibit as they see fit.

A text-laden timeline in an exhibition on Detroit’s Chinatown in the Community Gallery. Photo courtesy Detroit Historical Society.

This hands-off approach overvalues the open-ended creativity of participants and undervalues the utility of scaffolding and creative constraints. While not all institutions can afford the time required to make community galleries more co-creative, there are some simple things that staff members can do to improve the overall experience of community galleries for participants and audiences alike. They can:

- Provide tutorials or workshops on exhibit design

- Require community groups to include an artist or designer on their team

- Hold brainstorming sessions focused on creative forms of interpretation or interactivity

- Ask community partners to participate in evaluation of existing exhibits, to help them reflect on what does and doesn’t work

- Encourage community partners to prototype exhibits, or to incorporate visitor evaluation into their planning

- Incorporate creative challenges into exhibition solicitations that encourage specific interpretative styles and themes

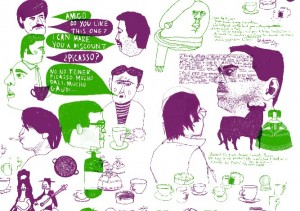

While community galleries are typically used to invite participants to create content unrelated to that displayed in other parts of the institution, hosting can also be used to invite outsiders to reflect on the role of the institution itself. In 2007, the Museu Picasso in Barcelona partnered with a local design university, Eina School of Design and Art, to set up an unusual community exhibition produced by illustration students.

The students’ professor challenged them to produce images that reflected an aspect of life at the museum. Twenty-six illustrators spent three months at the museum, watching how people used the gift shop, the bathrooms, and the galleries. In 2009, their resulting exhibition, Rethinking Picasso (Repensar el Picasso), was mounted in a small gallery. It featured a unique take on the institution and its functions.[9] The participants incorporated everything from the bathroom cleaning protocols to the guards’ circuits, to the scam artists hawking cheap souvenirs outside the museum.

By inviting artists to “rethink” the museum, the Museu Picasso ended up encouraging the illustrators to engage deeply with its many functions and idiosyncrasies. The result was an attractive exhibition presenting outsiders’ perspectives on the most intimate workings of the museum.

***

These last four chapters explored design techniques for developing contributory, collaborative, co-creative, and hosted projects. If your institution embarks on a participatory project of any type, how will you be able to confidently assert that it will enable you to accomplish your goals? To answer this question, we turn next to Chapter 10, which presents techniques for evaluating participatory projects and assessing their impact.

Chapter 9 Notes

[1] For an example of an institution that uses hosting to connect with nontraditional audiences around the topic of climate change, see the case study on The Wild Center in Chapter 1.

[2] See this tweet.

[4] To hear excerpts from a particularly delightful rogue museum podcast, check out Vital 5 Productions’ Portland Art Museum Unauthorized Audio Tour.

[5] Read Greenwalt’s June 2008 blog post, User Comments from Game Night.

[7] See comment number 7 on Aaron Schmidt’s November 2005 blog post, Another Successful DDR Night.

[8] For more information on the attendees and impact of 888, see Kevin Von Appen, Kathy Nichoaichuk, and Karen Hager’s 2009 paper, WeTube: Getting Physical with a Virtual Community at the Ontario Science Centre.